Over the several parts of this essay I’ve tried to explain just what I thought this grouping of “things” is that we create which is each artist’s view of how they look at their world. That I’ve dubbed it Art is only convenient for me to communicate my idea to you.

Over the several parts of this essay I’ve tried to explain just what I thought this grouping of “things” is that we create which is each artist’s view of how they look at their world. That I’ve dubbed it Art is only convenient for me to communicate my idea to you.

As we saw in the last installment though, there are times when we can’t be sure if something is Art even if were looking at it. We have to know the artist’s intentions and we don’t always know them. The water gets all muddy and suddenly we’re not even sure what’s real or imaginary, if Keanu Reaves is actually living in a virtual world on our computer, or if there’s even a point to it all. Now what?

Where’d Art Go?

There are times when, in my head, Art enters into some kind of Twilight Zone. Like physics, when we start looking too close, rules start to break down and stuff gets all weird and junk. Up is down, left is right, Madonna is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Art is Craft. And weirdest of all is when there seems to be no art at all when it should be right there before our eyes (or ears).

Take, for example, music. A composer has in mind an idea for a symphony. She writes down some notes while plinking them out on her piano and comes to some conclusion of how the piece is to sound. She then conducts an orchestra who plays it for an audience that cheers wildly and asks for an encore. But...where’s the art?

Is it in the music we hear? No, because the music is played with the intention that it is an exact copy of the symphony perceived by the composer. In the notes then? No, the notes are merely instructions for the musicians to follow to a tee. And, of course, any subsequent playing of the symphony is another copy, as well as any recording of it.

Or how about photography? Is the art in the moment the photographer snaps the shutter? In the negative in the darkroom? Surely these are both only steps in the process to get to the final art: the photo. But what if the intent is to make multiple prints with the idea that they are all identical? These are then copies – Craft. Again, where did the art go? Printmaking works in a similar way.

What if I create an illustration for a children’s book? I suppose that the single painting could stand alone as a work of Art. But if my intentions are that it is only complete when the illustration, along with all of its other illustration buddies, are paired up with the text, printed and bound into multiple copies of books...where’s the final art? Is it in the finished books? Isn’t this just the same as the print and the photo?

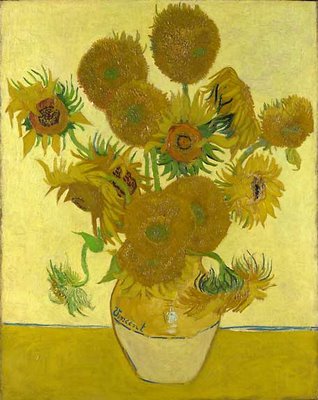

It would seem at times that Art is intangible. Even when we view van Gogh’s Sunflowers we aren’t seeing it as it appeared immediately after he painted it. The paint has dried and cracked. Maybe it’s even faded or acquired a layer of dust. We don’t see it as he intended it and cutting part of our ear off won't help. Like a song that lasts for only a brief time, Sunflowers too will disappear when the Sun expands into a red giant and chars everything on the planet to a cinder.

Sunflowers, Vincent van Gogh, 1888

Is it ever even possible to experience Art exactly as the artist intended it, anyway? Nope. We all have a lot in common but whenever Art is perceived by someone other than the artist it loses something in the translation. The only way we could fully experience what the artist means is if we share that experience, and we can’t do that yet. But that’s the one thing that all of these creative endeavors have in common. All of these interpretations of universes have an artistic experience associated with them. If we have something tangible to enjoy that we can call Art, well, that’s a bonus.

If we take it one step further, maybe we can have artistic experiences without even producing anything. Comedian Steven Wright had an interesting perspective when he said he was making some abstract Art. “Really abstract. No paint. No brush. I’m just thinking about it.”

Weird, indeed.

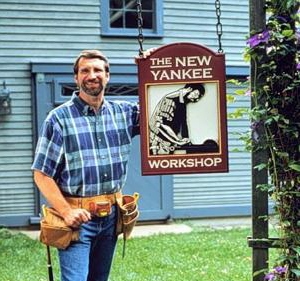

So, does that mean a craftsman is someone who just makes copies? Like when Norm Abram makes a copy of a chair in his New Yankee Workshop? Well, in a sense, yeah. If artists definitely are concerned with making interpretations of their universes, then craftsmen definitely are not. And if “Nahm’s” only interested in duplicating that Adirondack chair, then he’s not interpreting his universe. He’s copying someone else’s interpretation of their universe.

Let's say that Paul makes teapots. He makes really good ones that serve their purpose well, and that purpose is to hold my tea and keep it warm. And that might be the only purpose they serve. So his goal is to make sure that each teapot he constructs is as good as the ones that he’s made before. That is his intent. There is nothing about the teapot that would indicate he had any other intentions in mind. He has honed his craft at making a really good teapot. The teapot is a work of Craft.

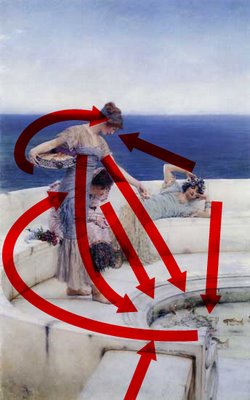

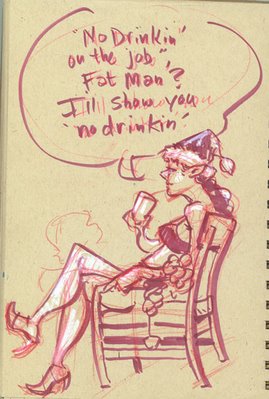

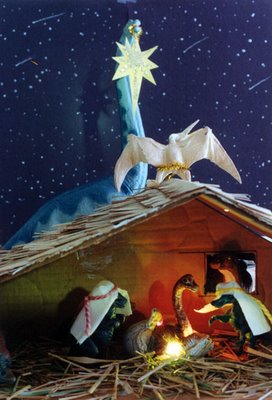

Suddenly Paul gets it in his mind to make something new like this: