Over the several parts of this essay I’ve tried to explain just what I thought this grouping of “things” is that we create which is each artist’s view of how they look at their world. That I’ve dubbed it Art is only convenient for me to communicate my idea to you.

Over the several parts of this essay I’ve tried to explain just what I thought this grouping of “things” is that we create which is each artist’s view of how they look at their world. That I’ve dubbed it Art is only convenient for me to communicate my idea to you.

As we saw in the last installment though, there are times when we can’t be sure if something is Art even if were looking at it. We have to know the artist’s intentions and we don’t always know them. The water gets all muddy and suddenly we’re not even sure what’s real or imaginary, if Keanu Reaves is actually living in a virtual world on our computer, or if there’s even a point to it all. Now what?

Where’d Art Go?

There are times when, in my head, Art enters into some kind of Twilight Zone. Like physics, when we start looking too close, rules start to break down and stuff gets all weird and junk. Up is down, left is right, Madonna is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Art is Craft. And weirdest of all is when there seems to be no art at all when it should be right there before our eyes (or ears).

Take, for example, music. A composer has in mind an idea for a symphony. She writes down some notes while plinking them out on her piano and comes to some conclusion of how the piece is to sound. She then conducts an orchestra who plays it for an audience that cheers wildly and asks for an encore. But...where’s the art?

Is it in the music we hear? No, because the music is played with the intention that it is an exact copy of the symphony perceived by the composer. In the notes then? No, the notes are merely instructions for the musicians to follow to a tee. And, of course, any subsequent playing of the symphony is another copy, as well as any recording of it.

Or how about photography? Is the art in the moment the photographer snaps the shutter? In the negative in the darkroom? Surely these are both only steps in the process to get to the final art: the photo. But what if the intent is to make multiple prints with the idea that they are all identical? These are then copies – Craft. Again, where did the art go? Printmaking works in a similar way.

What if I create an illustration for a children’s book? I suppose that the single painting could stand alone as a work of Art. But if my intentions are that it is only complete when the illustration, along with all of its other illustration buddies, are paired up with the text, printed and bound into multiple copies of books...where’s the final art? Is it in the finished books? Isn’t this just the same as the print and the photo?

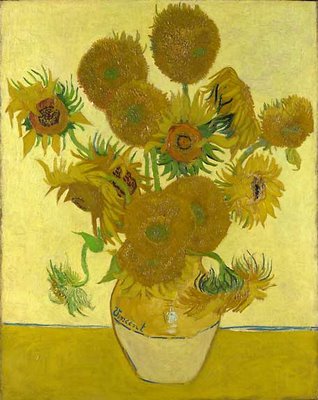

It would seem at times that Art is intangible. Even when we view van Gogh’s Sunflowers we aren’t seeing it as it appeared immediately after he painted it. The paint has dried and cracked. Maybe it’s even faded or acquired a layer of dust. We don’t see it as he intended it and cutting part of our ear off won't help. Like a song that lasts for only a brief time, Sunflowers too will disappear when the Sun expands into a red giant and chars everything on the planet to a cinder.

Sunflowers, Vincent van Gogh, 1888

Is it ever even possible to experience Art exactly as the artist intended it, anyway? Nope. We all have a lot in common but whenever Art is perceived by someone other than the artist it loses something in the translation. The only way we could fully experience what the artist means is if we share that experience, and we can’t do that yet. But that’s the one thing that all of these creative endeavors have in common. All of these interpretations of universes have an artistic experience associated with them. If we have something tangible to enjoy that we can call Art, well, that’s a bonus.

If we take it one step further, maybe we can have artistic experiences without even producing anything. Comedian Steven Wright had an interesting perspective when he said he was making some abstract Art. “Really abstract. No paint. No brush. I’m just thinking about it.”

Weird, indeed.

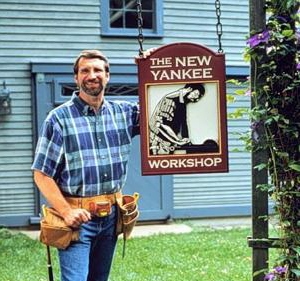

So, does that mean a craftsman is someone who just makes copies? Like when Norm Abram makes a copy of a chair in his New Yankee Workshop? Well, in a sense, yeah. If artists definitely are concerned with making interpretations of their universes, then craftsmen definitely are not. And if “Nahm’s” only interested in duplicating that Adirondack chair, then he’s not interpreting his universe. He’s copying someone else’s interpretation of their universe.

Let's say that Paul makes teapots. He makes really good ones that serve their purpose well, and that purpose is to hold my tea and keep it warm. And that might be the only purpose they serve. So his goal is to make sure that each teapot he constructs is as good as the ones that he’s made before. That is his intent. There is nothing about the teapot that would indicate he had any other intentions in mind. He has honed his craft at making a really good teapot. The teapot is a work of Craft.

Suddenly Paul gets it in his mind to make something new like this:

The Ronco Goodness Scale™

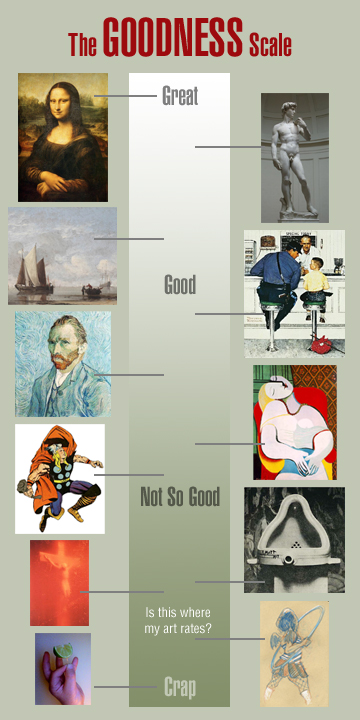

Once a month a group of Metro Detroit artists gather in a smoke filled bar in the hamlet of Hamtramck for a session of figure drawing called Dr. Sketchy. Models are culled from the local burlesque scene and we all pull out our pencils or whatever and do our best to capture the action in front of us. As an artist I am occasionally happy with my results and might proclaim a particular drawing my best from that night. To me it’s a good representation of what I see jiggling in front of me. So I call it good. And John sitting next to me might lean over and say, “Hey, that is good!” So it must be good right? But I might lean back over John’s sketchbook and say, “Maybe mine’s good, but I like yours better! It’s awesome!” Suddenly my drawing’s not so good as it was a moment ago.

If I flip back through my sketchbook and compare my sketch to others I’ve done in the past, it might lose even more standing on the “good” scale. It’s not that good at all now, is it? Then the Swag Faerie bypasses my “work of Art” as well as John’s and picks someone else’s to win a prize bag full of goodies. What the hell just happened? I thought mine was good? Apparently not.

It looks like our idea of what’s good is in comparison to other Art that’s out there for us to see. So, does that mean there is some scale to look at where Art is rated? One where the Mona Lisa sits at the top and where sticks with limes stuck on them are at the bottom? Where does something like Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain fall?

Above or below my work? Near the bottom though for sure, right? But why was his urinal voted the most influential artwork of the 20th century by 500 British Art professionals? Were they all full of it? Do I have to pull my scale out and compare my now apparently shitty Art with all other Art to determine whether it should just be tossed into the trash? Does that scale even matter?

Heck no.

It all depends on what situation in which we’re looking at the Art and by what criteria we judge its goodness. As music goes the Mona Lisa is crap.

“Wait,...what? Why would we even think to place the constraints of what makes good music upon a painting?!”

“Why?” indeed. I don't expect the Mona Lisa to offer me anything in the way of musical entertainment. Likewise, why would I compare my sketch of a hula-hooping zombie cheerleader to the Mona Lisa when all I want to know is how good it is in comparison to other work I’ve done?

A work of Art can only be rated good or bad by what we expect out of it. It’s highly subjective. Remember that the next time your young niece asks you if you think the picture she made for you is good.

So we ask, when confronted with Art we don’t like, “Why does anyone consider things like this to be good?” Well, why do people like Impressionist paintings? Back in the latter half of the 19th century Impressionism was thought of as a plague on the Art world. How dare these...these...Bohemians try to pass this crap off as Art? It all has to do with the intent of the artist again.

The intention of Impressionist paintings was not to strive to be like the academic paintings of the period that came before. As the name of the movement implies (which was only coined at a later date) the artists were attempting to capture the impression of light in nature - light that quickly changes. Eventually a number of Art critics began to appreciate what those wacky Impressionists were trying to say and concluded, “Hey, this is pretty good stuff. You should have a look!” And only then did Art museums begin hanging them on their walls.

Working in the Abstract

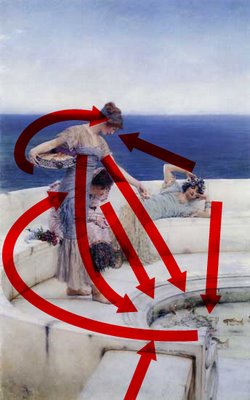

Again, it all depends on what an artist wants their work of Art to do. Art that tends more toward the abstract, like Scream by Edvard Munch, may not contain all of the information that say The Raft of the Medusa by Gericault contains. The Raft of the Medusa is like a novel, conveying to you not only the action in the scene, but also the shape and form of the figures as well as evoking feelings through the use of symbolism.

The Raft of the Medusa, Théodore Géricault, 1819

Scream, Edvard Munch, 1893

Scream is not concerned with all of that. It’s like a short story. It just wants to get one point across - the feeling of anguish that makes us want to scream - and it does it pretty well. That’s why it’s hanging in a museum, not because someone wants to “trick” us into liking crap. Munch didn’t paint it because he wanted to get rich quick. He painted it because he was trying to say something. Same for that pee-cross.

“But doesn’t the amount of work that goes into a work of Art add value to it?” Only if that’s what we expect from it. Duchamp submitted his toilet “ready-made.” No work went into it at all other than the brainpower used to bestow a meaning on it and a signature that wasn’t even his own name. But Fountain was picked as the most influential artwork of the 20th century anyway. So go figure.

Also, the amount of work involved in a work of Art isn’t always apparent so it’s difficult at best to use that as a measure of any universal goodness. Even though you might say that thousands of hours went into painting The Raft of the Medusa, thousands might have gone into painting Scream as well. You just don’t know that those thousands of hours were spent practicing on other paintings and trying to whittle the extraneous stuff down to what was only necessary to portray that feeling Scream evokes. Heck, some of those thousands of hours were probably spent in “research” - standing around screaming in anguish - so Munch might be highly qualified to try and capture that feeling in paint.

Artistic Environmentalism

It’s not only what a work of Art is trying to do that causes us to put a label of good or bad on it. It also depends on what environment the work of Art is viewed in.

I can place Vincent van Gogh’s The Yellow House next to a painting by popular artist Thomas Kinkade called Windsor Manor. Most educated individuals would pick the one-eared wonder over the commercial hack any day for many reasons. (Myself included.) But it’s an opinion based on what we expect from our paintings. And the word educated is the key. We only pick Vincent’s work because we know things about each of the paintings and make a choice about those things we deem more important to us. But what’s important to me isn’t necessarily important to everyone. That’s why there aren’t only tours to visit van Gogh’s birthplace in the Netherlands, but at Kinkade’s as well in swanky Placerville, California.

If we were to take both paintings by van Gogh and Kinkade and bury them in the sand for thousands of years until all reference to them had been forgotten, what might the people who unearth them conclude? Kinkade’s colorful houses might be more representative of something those people will understand. Based on the draftsmanship alone Kinkade could be considered the better artist. And he is the “Painter of Light” after all. Van Gogh’s buildings tend to be out of whack and out of correct perspective. He sometimes doesn’t even cover the complete canvass with paint. He’s sloppy. Kinkade’s got him beat as far as future archeologists and art critics might one day be concerned. So it all depends under what circumstances we judge Art.

Criticizing the Critics

That still doesn’t answer the question as to why we find things like urinals in museums - aside from the ones in the bathrooms. “Why do these Art critics, these elitist snobs, get to decide what goes on the walls of my government buildings?” Because we want them to.

Not that we want urinals as Art per se, but because there’s so much Art out there to wade through that we leave it to other people to conclude that some work of Art has enough value that it should be included in a museum’s collection. And occasionally that collection will include things that you personally just don’t like very much. Or things you don’t have any interest in understanding. Or things that you think should be used to stoke the museum’s furnace. It’s bound to happen. That’s fine. We don’t have all the same likes and dislikes. That’s one reason I don’t spend a lot of time in the Modern Art section of the Detroit Institute of Arts. I’d rather be looking at Impressionist paintings. But every once in a while I peek in and maybe learn something new.

It’s an Original!

As for Duchamp’s urinal, well...one thing we value in our Art above all is originality. The saying goes that there’s nothing new under the sun. Every once in a while, though, somebody comes up with a way of saying something with their Art that isn’t quite like anything else.

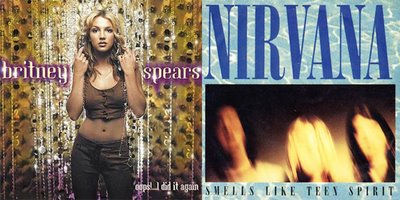

Using music as an example of originality, we all have favorite musicians that we like, but our group taste tends to recognize those who take a musical style in a new direction. Britney Spears may have had excellently produced CDs, but when it comes to originality, her music really offered little that was new or innovative. She may have been extremely popular and gotten kudos from the kids, but she doesn’t have universal appeal.

Conversely, Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit launched the rock movement dubbed Grunge upon the world. These guys were doing something we’ve never heard before; and, though it took time to catch on, their music influenced an entire new generation of musicians. Still, they don’t have universal appeal either. Ask your parents to listen to Kurt Cobain and his gang and they’re likely to tell you to turn down the noise.

Getting back to the categories of Art that end up in museums, usually the painting or sculpture types, they scream out for originality. And because the main function of museums along with the preservation of Art is to educate, it only stands to reason that they want to show us the best and most varied examples of Art available.

So after our trip to the museum or the rock concert, it’s now left to us to continue with our educations, to fill in the gaps. We usually fill in those gaps with other fine examples of work that, for whatever reason, appeals to us. On rare occasions we take a leap of faith and look into something we have no previous experience with. Sometimes we find nothing that appeals to our sensibilities, but other times we’re smacked betwixt the eyes and it opens up a whole new world for us. And we just might call it “good”. And for each of us, we’d be right.

Can anyone really look at a photo of a cup of urine with a crucifix in it and say it’s beautiful? Isn’t that what Art is supposed to evoke in us? A sense of beauty? I don’t know if it’s beautiful, but that all depends on whether Serrano meant for it to portray beauty in the first place.

Can anyone really look at a photo of a cup of urine with a crucifix in it and say it’s beautiful? Isn’t that what Art is supposed to evoke in us? A sense of beauty? I don’t know if it’s beautiful, but that all depends on whether Serrano meant for it to portray beauty in the first place.

When he gave it meaning with some intention, he gave it a job to do. That job might not necessarily have been to entice you to say, “That is the most beautiful photo of a pee soaked cross I’ve ever laid eyes on. And look at the lovely amber color of the urine! Where can I buy a print?” The function of Art isn’t always about what makes a pretty picture.

Since all Art is about intent, an artist might have several different functions in mind for her work to do. It can illicit some kind of emotional response such as happiness, sadness, or disgust in the case of the previously mentioned pee on Jesus. It might be trying to make a point or be representing an idea like that volcano painting or the red ping pong table. It may support someone else’s idea like a magazine or book illustration. Its purpose could be to entertain either an audience or the artist themselves. It can intend to be an inspiration for other art or an example of a genre. It can even be a means to gain approval or love, like the crayon drawings we plaster all over the fridge that we get from kids. And, of course, maybe the artist just made something to look pretty. The possibilities are endless!

How do we know the job the Art is supposed to be doing? Well, like the meaning of the painting it can come from the artist themselves. But also like the meaning, we may perceive it as being within the Art itself. We can look at a Tiffany stained glass window and probably get some kind of clue as to the job it’s to do. Maybe we get a sense of beauty from it. That’s its job, or at least one of the jobs the window is supposed to perform, as far as we can tell.

Girl with Cherry Blossoms , Louis Comfort Tiffany, c. 1890

We might not even know the job that the Art is supposed to be doing. This might be an accident when the artist hasn’t made his intentions clear and we miss something, or the work is misinterpreted. These things may alter the value we place upon the work. But sometimes the job might be to target a specific audience. You might not like Hannah Montana, but that might be because her music isn’t meant for you.

Just because it has a job to do, or someone approves of it, does that necessarily mean it has value? You may think its crap, but can it be appreciated for what it’s trying to do? Does it have any worth? Is it, dare I ask, any good?

Just because it has a job to do, or someone approves of it, does that necessarily mean it has value? You may think its crap, but can it be appreciated for what it’s trying to do? Does it have any worth? Is it, dare I ask, any good?

Next time: Why Is This Crap Hanging In A Museum?

Just what did Barnett Newman intend when he painted Be I back in 1970? How can we know what those intentions are, what his painting is supposedly about, if its meaning doesn’t immediately smack us in the face when we see it? Can we only consider some work a piece of Art if it doesn’t require us to read a novel to understand it?

Just what did Barnett Newman intend when he painted Be I back in 1970? How can we know what those intentions are, what his painting is supposedly about, if its meaning doesn’t immediately smack us in the face when we see it? Can we only consider some work a piece of Art if it doesn’t require us to read a novel to understand it?

Next time: Function Junction